The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Gunset Training Group or its affiliates.

Click HERE to view the original post on the GunSnobbery Blog

Author’s note: this is part 7 in a series of educational posts I am going to write about State of Ohio and federal weapon and firearm laws. Part 1 can be found here. This post does not offer legal advice. I am not a lawyer. I am a Certified Firearm Specialist through the International Firearm Specialist Academy and the State of Ohio certifies me to teach Ohio’s weapon laws in the Basic Police Academy. I’ve spent quite a bit of time studying federal law and Ohio’s laws in 30 years on the job. More than anything, this series of posts is an attempt to educate people on portions of the law and to show them where they can find the laws so that they can educate themselves further. Please consult with an attorney who specializes in firearms and weapons law if you have questions that require a legal opinion. If you are a law enforcement officer, check with your jurisdiction’s legal counsel for guidance. And remember, not all attorneys are created equal. And keep in mind that laws, interpretations of laws and definitions change. So what was current at the time I published this article may have changed over time.

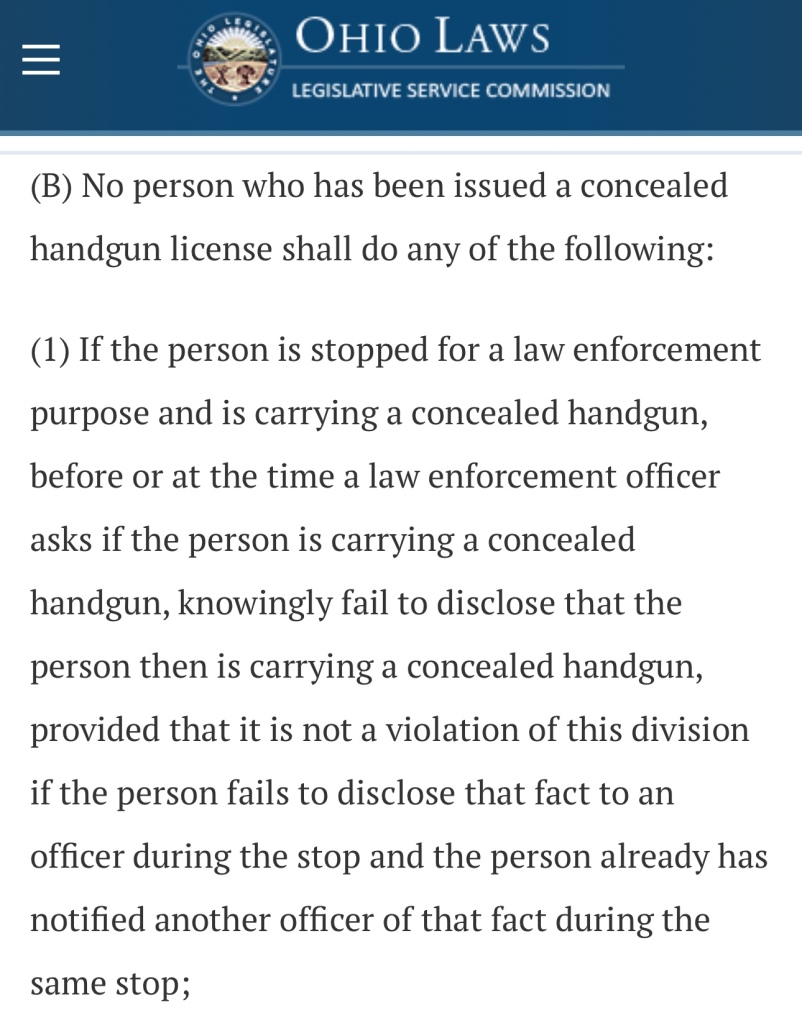

If you haven’t read the first article covering Carrying Concealed Weapons – Ohio Revised Code 2923.12(A), it can be found here. 2923.12(B) is all about dealing with the police. This section has changed (for the better) over the years, but still has some language of which I am not a fan. While 2923.12(A), in general, applies to everyone, (B) only deals with a certain group of people – people who are legally carrying a concealed handgun. Now, remember from this article that when you see language in the Ohio Revised Code that talks about someone who “has been issued a concealed handgun license”, it also refers to “qualifying adults” who are carrying under Ohio’s permitless carry law.

(B)(1) is about notifying an Officer that you are armed. This is one of the sections that has been changed significantly over the last 20 years. Fortunately, the requirement that a person notify “promptly” (a very subjective term) was removed several years ago. However, there are still issues with this section that can be troublesome. The main issue? What does “stopped for a law enforcement purpose” mean? I wish I could provide you with a definitive answer, but I can’t. It is not defined anywhere in the Ohio Revised Code. Nor have I been able to find an Ohio court that has defined this phrase in a court opinion. I can tell you what I think it means, but I’m not a Judge or Court. And their opinion is all that really matters. The way I look at it, “stopped for a law enforcement purpose” means that the person I am dealing with is detained and not free to leave. If you are free to end the interaction with the police whenever you want (like if you called to make a police report), then I don’t see that as being “stopped” under the meaning of this statute. But I’m only one cop out of over 20 thousand in the state. The state lesson plan used in the basic police academies across the state does not address, discuss or explain what “stopped for a law enforcement purpose” means. And since neither the courts (at least that I’ve been able to find) nor the legislature have chosen to address this, then whether you are “stopped” or not is a subjective standard up for many different interpretations. The safest bet? Assume the Officer believes you have been “stopped” if they ask you if you are armed and answer truthfully.

Additionally, if you do have a concealed handgun license, realize that fact will show up in a records check anytime an Officer runs your information through the state database (called LEADS). Some Officers are under the mistaken belief that you must notify them that you have a concealed handgun license under any circumstance. But the law is clear – the notification requirement applies only when you are actually carrying your handgun.

And last, the law has been changed so it now only requires you to notify the first Officer that asks. If you fail to notify other Officers it is not a violation.

Sections (2)-(4) codify what should be common sense decisions when interacting with the police – keep your hands in plain sight, don’t touch or try to touch your pistol and obey all lawful orders. There is a potential pitfall when you look at the language of these sections – “after any LEO begins approaching the person…..” What does that mean, exactly? I don’t know, so I would suggest erring on the side of caution when you see that language. I actually had to go testify against one of my former students years ago for a violation of (3). Fortunately for him, the jury came back with a not guilty verdict. But erring on the side of caution may save you some money defending yourself in court.

One of the questions I have received over the years is “what is a lawful order”? I will cover this again when we cover 2923.16 – Improper Handling of a Firearm in a Motor Vehicle, but since the most common type of encounter with law enforcement is a traffic stop I want to discuss it here as well. The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) has made several rulings over the years that deal with lawful orders on traffic stops. In Pennsylvania v. Mimms SCOTUS gave Officers the ability to order drivers out of lawfully detained vehicles for officer safety reasons. Just because we want to. So asking an Officer why they want you to step out of the vehicle is irrelevant. SCOTUS extended that ability to passengers in the vehicle in Maryland v. Wilson. This applies to any traffic stop, whether or not you are carrying your pistol. If you aren’t carrying your pistol and you refuse to exit the vehicle, you can still be criminally charged, just not for this section. It would probably be a charge for Obstructing Official Business – 2921.31.

Although it does not expressly say that officers can disarm you when you are “stopped for a law enforcement purpose”, the Ohio Revised Code does imply that disarming would fall under the “lawful order” umbrella when you look at other parts of the statute. 2923.12(G) expressly states that if you are disarmed, your pistol must be returned to you at the end of the interaction unless certain conditions apply.

Those conditions could be:

- The pistol is contraband (like a zip gun)

- The Officer charges or arrests you for something where the firearm may be evidence (road rage investigation, etc.)

- The Officer determines you may not legally possess the firearm (a recent protection order was issued, etc.)

As I mentioned in this article the default “setting” of 2923.12 is that people cannot carry concealed deadly weapons. Exceptions to this restriction pop up in sections (C) and (D) of 2923.12. (C), for the most part, is easy to understand. Exceptions include law enforcement and other government employees who are authorized to carry firearms. There is also an exception for people who have been issued a concealed handgun license that covers carrying handguns that are not dangerous ordnance. And remember that this exception would also cover people who are “qualifying adults” that we discussed in other articles. But this exception does not cover carrying anything except handguns.

The circled portion of the section is important for concealed handgun licensees, active duty military members, and “qualifying adults”. I haven’t talked about prohibited carry zones yet, but 2923.126(B) talks about prohibited carry zones. In these prohibited zones, the exception used for concealed handgun licensees, active duty military members and “qualifying adults” does not apply. The next article will cover these prohibited carry zones.

To carry under this exception, active duty military members must show military ID AND proof of training that meets or exceeds the requirements necessary to get a concealed handgun license. I, personally, never came across anyone on active military duty that carried that documentation, but as far as I was concerned active duty military met the requirements and I never asked for further documentation. Just know that if you are active duty and carrying under your military credentials, then you need to carry that training documentation. Having said all of that, chances are that active duty military may also be a “qualifying adult” so there is a way around not having the correct documentation.

As you can see above, there are also exceptions for transporting firearms in vehicle and possessing them in your home. I will spend more time talking about vehicles in a future article.

The last thing I will discuss in this article is section (D). (D) has been around, in some form, for decades. Prior to 2004, (D) was the only way that average citizens could (hopefully) justify carrying a concealed weapon because state law did not otherwise provide for it. It is important to note that (D) cannot be used to justify carrying a concealed handgun because there are other legal means of carrying a concealed handgun. So this “affirmative defense” can only be used to try to justify carrying a concealed deadly weapon like a knife (assuming the knife was being carried or used as a deadly weapon) or a slap jack or brass knuckles.

So what is an affirmative defense? In layman’s terms it is a way for someone to avoid being charged or convicted of behavior that otherwise would be a crime. Self-defense is also an affirmative defense. For example, if I shoot someone it would be a crime, unless I was successful in arguing the affirmative defense of self-defense. For this section – (D)(1), what it boils down to is that the accused would argue, “yes I was carrying brass knuckles concealed, but I should not be charged/convicted of CCW because of the circumstances surrounding my job, a prudent person would feel the need to go armed to protect themself”. This is often called the “prudent person” defense. A great example would be a jeweler who goes to various places to sell and buy diamonds and gold and one of those places is a pawn shop in a bad part of town. Especially if the jeweler has been robbed previously.

(D)(2) does not involve someone’s occupation, but could be used in another type of situation where, due to the circumstances, a prudent person would feel the need to carry some form of deadly weapon for protection. An example of this section could be a situation where the person carrying the deadly weapon has been the victim or witness to a crime and has received death threats from the suspect or the suspect’s family. Why not carry a gun, you ask? Well, there could be a variety of reasons. For one, what if the person works in a place, or goes to a church that prohibits the carrying of firearms? I had a student years ago who worked at the local military base. She was not allowed to carry a firearm onto the base. She was concerned her estranged husband was going to kill her (a valid concern, he’s in prison for trying to hire a hitman to kill her), yet the best means of protection was denied to her. So I helped her buy and learn how to use a Taser.

I think (D)(3) is pretty self explanatory so I won’t spend time on it.

Here is the problem with this particular affirmative defense when it comes to carrying concealed deadly weapons – the judge has to agree with you before he lets the jury hear about the affirmative defense in the jury instructions. If the jury does not hear about it, they may not consider it during their deliberations. Which can be the difference between a guilty or not guilty plea. Here is a great example of an affirmative defense argument that did not make it to a jury. In that case, the person was convicted of CCW. I have said it before, it is ridiculous that a law abiding person can carry a pistol for self-defense, but not another type of deadly weapon.

In the next article I’ll go into detail on the prohibited carry zones…….